© Sara Davis

Downpour

Tropical Storm Fay rolled in the week after Independence Day. Usually storm number six doesn’t make landfall until August, but you might say that 2020 was a tempestuous year.

That Friday, it rained all day. Marooned in South Philadelphia without a car, I watched from my window for a break in the sheets and torrents spinning off from the early-season cyclone. Before my local bakery closed for the weekend, I needed an offering of gratitude for my colleague who was packing up my office computer and ferrying it across the city so I could work at home. By July, my own laptop was failing from overuse.

I thought I saw the storm soften, so I took a chance and dashed up the street. I heard the rain pick up speed before I felt it, rapping staccato on the trash bags piled along the sidewalk. I was soaked from the shoulders down when I reached the tiny shopfront. Another customer already waited inside, masked, so I stood in the gusty rain under a useless umbrella to wait. I held the door open for her as she left, opening an iridescent umbrella like a shield. By the time I had the conciliatory babka wrapped and nested safely in my bag, the rain had slowed again. The sidewalk was empty, except for the trash. The iridescent umbrella was blowing in the street.

Oscillation

I am not a scientist. My job is to write promotional copy for a sprawling university, a green campus in the heart of Philadelphia, as the brochure says. In the beginning of 2020, the campus was not so much green as muddy gray, the color of rain-soaked concrete. I left my heavy winter coat in storage during an unusually wet and balmy January. The pleasure of walking outdoors without slipping on ice became knotted with an uneasy apprehension about the same, and I enrolled in my first science class since high school. I wanted to understand the changing weather.

Here is the CliffsNotes version: the average global temperature is rising, the oceans are warming, dry regions are getting drier, wet zones are getting wetter, storms are getting stronger and less predictable, and another decade of rampant energy use could tip the planet into a “hothouse Earth” scenario. Wait, sorry, that’s climate: clear, devastating, long-term patterns of change. Weather is more elusive, harder to predict.

It didn’t snow over Christmas in Philadelphia that year. The atmospheric pressure was extremely high over the warm waters northeast of Morocco and extremely low in the stormy seas near Iceland, two critical points that influence weather across the entire North Atlantic. The steep difference between those points caused the jet stream to flow strong and fast, hurrying cold temperatures past the East Coast. This is okay, I reassured my friends during that mild winter. Yes, the planet is getting warmer, but the North Atlantic Oscillation changes year to year. It will snow again.

And so it did. Spring was just starting to show in Philadelphia, relieving the long wet winter and nearly two months of social isolation, when a frigid streak of polar air plunged southward. A blanket of snow fell over New England in May 2020.

The steep pressure gradient can have other side effects, too. With more rain and higher temperatures, the Atlantic Ocean warms and loses salinity. The sea level rises. Hurricanes change course.

Cyclones

I spent the first 24 years of my life cradled by the Mississippi River, first in the floodplains of west Tennessee and then in the basin of New Orleans. I moved to Philadelphia at the height of summer in 2005, and most of my early conversational gambits involved the weather. Y’all don’t know about heat. In Memphis, kids spent the first three weeks of every school year fainting and vomiting from the heat. By the end of August, everyone wanted to talk about Hurricane Katrina, those who left and those who stayed. Y’all don’t know about evacuating from a water-bound city, I argued. You get bottlenecked on the narrow causeways. You drive overnight in Mississippi and pass hotel after hotel with no vacancies. Small wonder I was slow to make friends.

The first time I heard a tornado warning in Philadelphia, I scoffed. Y’all don’t know about tornado weather, I texted nervous friends. Tornado weather is green sky, sirens. Double doors clanging open as kids crouched by their lockers, hands cupped protectively over their necks. The highest point in my old neighborhood, a steeple, plucked off the church and smashed like a flower on the street.

Fifteen years later, when I hear a tornado warning in Philadelphia, I text my friends the best places to take shelter at home. The extreme weather I grew up with is here now. Hotter summers have crept north, and Philadelphia too is tornado country.

Dust

During the first pandemic summer, I tended to a few heat-blasted flower boxes mostly occupied by sun-striped hostas and creeping jenny. Every week a rangy street squirrel dug up last spring’s tulip bulbs and discarded them, uneaten. Every week I replanted them. It’s rare but not impossible for tulips to bloom for a second season; I banked on being an exception.

I threw the weeds into a bucket with coffee grounds and eggshells. I didn’t need compost for my postage-stamp garden, so my bucket is emptied weekly by a local company that promised my kitchen and garden detritus would find a new life where they are needed. Farms, maybe. The organization that coordinated my biweekly grocery delivery partnered with the compost company, and I liked to imagine that my solitary habits connected me to a larger ecosystem. From dust came these radish tops; unto dust they shall return. Otherwise, the world felt very small that summer. Nations around the globe closed their borders to American travelers as coronavirus cases surged. I only traveled as far as I could walk, anyway.

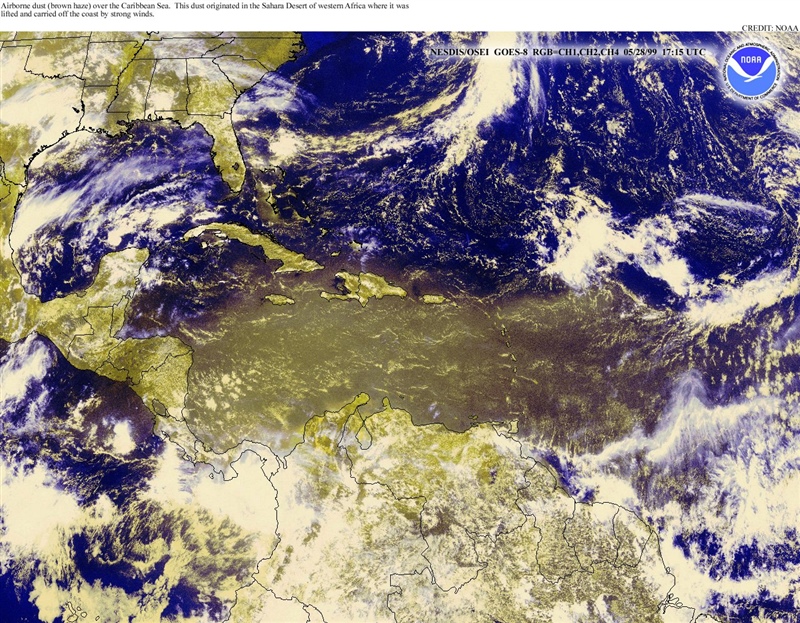

Travel was banned the same month that a massive dust cloud drifted from the Sahara all the way to the Gulf Coast. What rises into the atmosphere does not respect national borders; like it or not, we all breathe the same dust.

Ozone depletion

In March 2020, a new hole opened in the ozone layer over the Arctic. That happens sometimes, although not usually at the North Pole. The same steep atmospheric pressure gradient that kept winter mild on the East Coast also caused the polar winds to whirl faster, trapping extraordinarily cold temperatures at the top of the world—so cold that water vapor crystallized all the way up in the stratosphere, forming a frosty canvas for chemicals carried up from the surface. Energized by the tentative spring sunlight, those chemicals began to react with ozone molecules, breaking them apart.

In April 2020, the Arctic ozone hole snapped closed. That happens sometimes, too. In fact, changes in the stratospheric ozone layer is how we know climate policy can work: decades after we banned ozone-depleting chemical compounds from our air conditioners and hairspray, the most famous ozone hole over the South Pole almost closes during its dark season. Success stories are important in climate discourse; otherwise, the mind resists. We look for exceptions, a reason to remain optimistic.

Some climate scientists predict that the Antarctic ozone hole will disappear entirely by the year 2050. Some climate scientists predict that certain coastal cities could disappear by the same year.

Explosion

In 2015, my path crossed with the CEO of an energy company who had recently purchased an old refinery in southwest Philadelphia. I wrote promotional copy for a trade services organization that planned to present him with a global leadership award. Prepare for protestors at the ceremony, my colleagues warned. Use the back entrance. I was emerging from a miasma of depression that year, disoriented by the noise and glare of politics. I knew the protest had something to do with the CEO’s lobby to build a natural gas pipeline across half of the state, but fumbled for the right questions to ask. What was the problem with pipelines again? What did this have to do with the refinery?

The refinery exploded in June 2019, hurling literal tons of hot metal and hydrofluoric acid into the air. I heard the boom from my apartment, one mile away. The flames burned for a day, while refinery and city officials swore that the air was safe to breathe. Incredibly, no one was killed.

I wish I could say it was this fiery explosion that blew my mind, the clear and urgent threat to my community that ignited my passion to learn more and take action. But the way the mind moves is like the weather: easy to talk about, difficult to predict. Easy enough to look back and think, oh, yes, the warning signs were there. Harder to look ahead, or even at the present, and see where the patterns lead.

But the dust and shrapnel and torrential rain are falling whether we understand them or not. These are the only stories I know how to tell anymore, and they all end in the same way: with change.

Sara Davis is a recovering academic and marketing writer who lives in Philadelphia. She recently completed a Certificate in Climate Change and an Advanced Certificate in Creative Writing from Penn, and her PhD in American literature is from Temple University. Recent publications include “Closure” (Vignette, July 2022), “Ever Given” (Cleaver Magazine, Summer 2021), “How to Escape a Time Loop” (Okay Donkey, November 2021), and “The Untimely Collaborators,” a braided essay that won one of two Editor’s Choice awards in the 2020 inaugural CRAFT Creative Nonfiction contest. She has previously published essays on food history and culture.

As a writing professional, Sara has created long-form blog content for arts and education organizations, style compliant and search engine optimized website copy for nonprofits, and book reviews for independent publishers. On her own time, she blogs about books, video games, culture, and climate change.